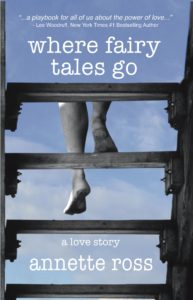

Guest Blog Post: Where Fairy Tales Go by Annette Ross (Book Excerpt)

“On January 4, 2000, my sweet husband Bill and I kissed our toddler Natalie goodbye, with promises to be back soon as we headed to the hospital to deliver our second child. Twenty-four hours later, we had a newborn daughter, but all else had been horribly, irrevocably changed. Life had thrown me curves before, but none like this.”

“On January 4, 2000, my sweet husband Bill and I kissed our toddler Natalie goodbye, with promises to be back soon as we headed to the hospital to deliver our second child. Twenty-four hours later, we had a newborn daughter, but all else had been horribly, irrevocably changed. Life had thrown me curves before, but none like this.”

Annette Ross shares her incredible story in the inspirational memoir Where Fairy Tales Go. This dynamic mother of five describes her personal challenges, financial struggles, and the life-altering medical error that left her unable to walk. Join Annette and her family on this journey to reclaim a lost fairy tale.

January 2000

“Do you know what has happened to you?” he asked, as if he was anxious to deliver the bad news. “Not fully,” I replied. “You may never walk again,” he said somberly.

“Do you know what a spinal cord injury is?” he asked. I didn’t, but knew instinctively it wasn’t good. He explained that the injury was not reversible, there was no going back, and it would be a long road. “That can’t be true,” I said, as I looked down at my legs. I started to touch them, rub them, almost hug them with my hands. They belonged to me, and I depended on them to move. I had no faith in this doctor’s words. He didn’t know me. I didn’t believe for a moment that my body would betray me. I would heal.

I felt a flicker of hope each morning when the team of neurologists arrived at my bedside, armed with a coffee cups, clipboards, and pens. After a spinal cord injury, it’s a positive sign if you can begin to move a toe—and the sooner the better. The residents would pull back my sheets and instruct me, “Wiggle your toes.” I tried. I mean to say I really tried. My toes did not cooperate. My brain sent the signal. I could think the thought, but my body remained perfectly still. The young doctors jotted notes and looked at one another ominously. They’d never heard of an epidural causing paralysis before.

After the residents left, their leader, Dr. Stephen Strittmatter, would often stay behind. A specialist with a lengthy list of impressive credentials, he was soft spoken and reserved, but also deeply compassionate. He spoke to me as a big brother would, and I felt that I was more than a diagnosis to him. He confided that having me there was a reminder that a real person would one day benefit from their sustained efforts. He described in simple, layman’s terms what he saw on the films. He drew many pictures. He brought the MRI images to show me exactly where my spinal cord had narrowed.

“That’s my problem? You must be joking!” I thought that whatever was inhibiting my use of half my body would show up as something more obvious. But no. In the lower portion of my back, there was a place where the cord was a hair’s-width thinner than the rest, and that was it. A nonevent if you ask me.

“There are no cures?” I pleaded. He was patient with me. I asked the same question every time I saw him, and each time he responded evenly, without the slightest hint of frustration. “We have made progress, and you might make some strides through therapy, but as of now, no, there are no cures.” He looked to see if I understood him. I did; we did. Not knowing what else to say he squeezed my hand and left the room.

***

Three weeks earlier, Bill and I had known exactly what lay ahead for us—life with a toddler and her newborn sister, a wonderful new home, a successful business, exceptional friends, and the excitement (and exhaustion) of balancing motherhood and graduate school. I’d picked out a light-blue checkered fabric for the chair in Anna’s room. Her changing table was stocked with diapers, wipes, and pastel-colored onesies. The musical mobile hung quietly over the crib waiting to sing to its new arrival. We were all ready, including Natalie, who talked non-stop about her plans to care for her baby sister. We were truly blessed.

Three weeks earlier, Bill and I had known exactly what lay ahead for us—life with a toddler and her newborn sister, a wonderful new home, a successful business, exceptional friends, and the excitement (and exhaustion) of balancing motherhood and graduate school. I’d picked out a light-blue checkered fabric for the chair in Anna’s room. Her changing table was stocked with diapers, wipes, and pastel-colored onesies. The musical mobile hung quietly over the crib waiting to sing to its new arrival. We were all ready, including Natalie, who talked non-stop about her plans to care for her baby sister. We were truly blessed.

Now, my baby and I were both in diapers. I’d pictured rocking her in the early morning light, gazing out at the white pines beside our house. Instead, we shared a sterile, brightly lit hospital room. How was I going to care for her? Or for my little Natalie, waiting at home? The hospital made arrangements for Anna to come stay with me in the special-care-maternity wing. She arrived the day after my transfer. Natalie was being well looked after by my parents. Because I was being pumped full of steroids and other toxic chemicals, my breast milk was tainted, and Anna was not allowed to nurse. Once things improved and the doctors decreased my meds, I tried to pump—the nursing staff understood my desire to bond with Anna—but the milk never came in successfully. I felt such contempt for my body.

When she entered the world, Anna should have been center stage. Instead, she became the opening act and then the backdrop to the drama of my legs. During the day, a multitude of doctors and nurses cared for me, commanding much of my attention. It seemed that, any time I tried to focus on Anna, someone would enter the room to draw a vial of blood or administer a heparin shot. She was such a great baby. It was as though she understood at the tender age of 1 week old what we needed from her. She slept well, rarely cried, and sweetly cooed for anyone who gave her the attention she deserved.

* * *

September 2012

I sat in the bathroom staring at another positive pregnancy test. It was the night of Natalie’s first high-school homecoming dance and her friends were at our house, wearing short dresses and high heels and looking gorgeous. There was general excitement in the air, but I was locked behind the door, panicked. Should I scream? Cry? Risk telling an already miserable husband? Once Nat left with her friends, I broke the news. “Bill, I need to tell you something, but please do not be upset.” He always hated when I said that. And, to be sure, Bill was shocked, maybe too shocked to be upset.

“Show me the test.” He went right out to buy another test so we could be sure. The results were consistent. He shook his head, hugged me, but said very little. A few minutes into his disbelief he asked, “How do you feel?” His concerns always centered around me. “Do you think this will be okay for you?”

I shrugged my shoulders. How could I know? Always somewhat fearful of my post-injury pregnancies, I admitted, “I am scared, Bill. I can only think this will not end well.” But he would never say no to life. Despite the precariousness of our situation, Bill was not going to try to sway me one way or another. Like he has done throughout our long relationship, he lets me be me. I can’t say I always do the same. This latest pregnancy made me feel as if we were being tested again, and I asked him what he thought.

“I don’t think of it that way, Annette. I only know I would not change any aspect of our life if it meant we would not have the girls.” But he did not have the worry of a pregnancy. Could I do it? Endure nine months of worry at a time when so many things were uncertain? The miscarriages of 2007, 2008, and 2009 were not at the forefront of my thoughts any longer. I did not miss the sorrow. The raw feelings I had finally compartmentalized soon resurfaced. Our entire household was too fragile to take this on, I thought. It was not a good time to have a baby.

A friend of mine had recently given birth to a delightful baby girl. Whenever I saw them at church, I longed to squeeze those sweet baby cheeks but when she would start to fuss, I was relieved that our kids were past the stage of diapers, nursing, and sleepless nights. That said, if someone were to drop a baby at our door, would we not take it in? The short answer was yes. It wasn’t that I did or didn’t want a baby. I was 45-years-old and the thought had not seriously crossed my mind in years. My heart said yes.

A friend of mine had recently given birth to a delightful baby girl. Whenever I saw them at church, I longed to squeeze those sweet baby cheeks but when she would start to fuss, I was relieved that our kids were past the stage of diapers, nursing, and sleepless nights. That said, if someone were to drop a baby at our door, would we not take it in? The short answer was yes. It wasn’t that I did or didn’t want a baby. I was 45-years-old and the thought had not seriously crossed my mind in years. My heart said yes.

Annette was born in Chicago, graduated from Sarah Lawrence, and lives with her husband and five daughters in San Diego. She has been a board member of the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation and is a proud model in the Raw Beauty Project. Where Fairy Tales Go is her first book. Annette had her youngest at 46 while she was struggling financially and in a wheelchair for 13 years.

Tags: annette ross, christopher and dana reeve foundation, having a child after 40, later mom, wheelchair