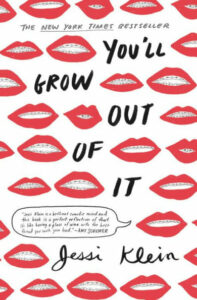

You’ll Grow Out Of It by Jessi Klein (Book Excerpt)

From YOU’LL GROW OUT OF IT by Jessi Klein. Copyright © 2016 by the author and reprinted with permission from Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

From YOU’LL GROW OUT OF IT by Jessi Klein. Copyright © 2016 by the author and reprinted with permission from Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

TRYING

I have always hated the phrase We’re trying, which couples generally use to describe their attempts at conceiving a child. I used to think it was because of the slightly prissy euphemistic quality of it, the substitution of the wan trying for fucking; but when I thought harder about it, I realized maybe it’s because trying evokes so much struggle; in a way, it’s the opposite of a euphemism. Maybe it’s all too accurate, and what I don’t like about it is how graphically it paints a portrait of two people joylessly having intercourse in an attempt to breed.

Trying.

I’d made up my mind long ago that I would never be one of those ladies who was trying. It sounded so sad and desperate, and I wasn’t sad and desperate. I’d never wanted a baby. In my mid-thirties, I thought this primal urge might kick in, but it didn’t, and I was glad it didn’t because then I would become someone who talked about trying. Or even worse, blogged about it.

By my late thirties, I still didn’t want a baby. At most, as forty approached and became an increasingly realer number that was probably going to happen to me at some point in the terrifyingly near future, I had a dim feeling that it might be nice to have a kid when I was old. More specifically, I would think about being on my deathbed (I’m fun), and how if there was no kid, it would be sad and lonely (for me—I didn’t think about how the kid would feel).

So basically, when I imagined having a kid, I projected forty years into the future, in which I visualized a fully-grown adult spoon-feeding me pudding on my way out of this earthly door. I wasn’t worried about feeling a kid void before this life moment.

Then I got married.

Before we got engaged, Mike and I had a few vague, hypothetical conversations about whether we would have a kid. I very clearly remember that in all of these conversations, we were both on the same page, which is to say we agreed we were completely ambivalent. Then, about a month after our wedding, it came up again, and magically, Mike had a different memory of our conversations. Somehow, he remembered us both saying we would definitely have kids. As you might imagine, this led to a rather large fight, in which I tried to remind him that our favorite activities were going to restaurants and drinking, two things that most certainly would be curtailed by the presence of a child. I challenged his recall of how I’d phrased my interest in us having a baby. I’d always said I loved our life, that it was hard for me to picture the disruption of our rambling routines. He ended up storming out of the house and I retreated to our bedroom to look at pictures of corgis on Pinterest.

I knew it was inevitable, with Mike feeling so strongly about it, that we were going to have a kid. But we’d just gotten married. I didn’t want to try yet. I was thirty-eight. I thought I probably had some time left. Halle Berry had just gotten pregnant again and she was like a million years old. I was scared of how everything would change once we had a kid. I thought maybe we could at least wait till the summer. I kept thinking to myself, This is the last year of my life. I repeated that phrase in my head—last year of my life, last year of my life. I better enjoy it, it’s the last real year of my life. And I would say to Mike, This could all be moot you know, maybe I’m already too old, maybe I’m barren. Barren is a fun word to toss around with your husband when you’re being a real fucking jerk. But I was just making excuses; I knew I wasn’t barren, because my mom had three kids, and she had my little sister when she was thirty-six, which is basically the same as thirty-eight.

Still, the next time I went to see my ob-gyn, I figured it wouldn’t be a bad idea to ask her, in her professional opinion, how long I had to wait before I had a kid (instantly, with no trying). Again, I wasn’t worried because at that moment Halle Berry was expecting and she’s sixty-four I think? I knew I wouldn’t be able to wait quite that long, but I thought maybe I could wait as long as some other celebrities I’d read about in my trash magazines.

A quick word about my doctor, Dr. Sani. She’s incredibly hip. I know she must be older than me, but she looks about five years younger. She grew up in New York, went to the same high school as me, and used to do a little deejaying in college. She’s compassionate, she never rushes you, and she’s delightfully down to earth. She’s also gorgeous. This can be a problem since I always miss a small portion of her advice while I am entranced by her curtain of perfectly shiny thick black hair.

At the appointment we spent the usual time gabbing about my job and the weather and vacations, and I stared at her hair a bit. When we got up to babies, as expected, she didn’t seem overly concerned. “Most thirty-eight- year-olds can get pregnant without too much trouble. The problem is usually more with staying pregnant.” I ignored the second sentence.

It was December at the time. She thought if I wanted I could wait till the end of the following year. That felt like enough time to live the last year of my life. She went on to suggest that if we wanted some peace of mind, I could do a relatively new but simple blood test that would measure a hormone called AMH. She explained that it measured the quality of your egg reserve, or maybe it was the quantity, I was never totally sure (again, staring at her hair). We’d done other blood tests and she felt optimistic I was in good health and had nothing to worry about. She left the room and the nurse came in to take my blood and I went home and stopped thinking about babies entirely. I had the slightly smug feeling you have when you know you will be fine because you’ve always been fine.

A couple of weeks later, she called to tell me that I needed to redo the test. “The number that came back didn’t really make any sense,” she said, “and then I found out that they didn’t freeze your sample in transit. Let’s not worry about it. I’m sure it’s fine, just redo it.” For about sixty seconds after we got off the phone, I replayed the sound of her voice, trying to discern if she was genuinely unconcerned or was hiding something. I used the same filter I use when I’m flying and I need to look at a flight attendant to assess whether turbulence is going to kill me or not. I decided to believe her.

A few days later, I go to a lab to have my blood taken again. I make calm casual conversation with the woman who will be taking my blood so she will know I’m not a puss about having my blood drawn (I’m a giant puss about having blood drawn). I walk out of there feeling very confident that this version of the test will confirm that I am totally healthy and can probably wait as long as, if not Halle Berry, then maybe Salma Hayek (first child at forty-one).

A couple of weeks later, I am at an edit facility, watching cuts of the show I write for. It is near the end of the day. My phone rings. It is my doctor. This time, even though she is, as always, professional and calm, her voice does not completely pass the flight attendant test; at best the cabin is out of white wine. At worst an engine is sputtering.

“Your numbers did not come back exactly where we’d want them to be,” she began to explain.

My cell reception was not good and I did not have privacy. I kept moving from one dark exit stairwell to an- other, trying to hear her as she explained, in so many words, that I would become a woman who would not only have to try, but would have to try very, very hard. She had wanted my number to be at least a 2. Instead, my number came back as <.16, which is the lowest the test can measure before your ovaries are emitting a life signal so weak it can no longer be quantified.

As she spoke, for the first time in my life, I felt as if a ghost were passing through me; that someone else, some infertile, trying and failing sad person, had mistakenly crossed their fate with mine. This can’t be my life, I kept thinking, even though it now most definitely was.

And the other thing I suddenly couldn’t stop thinking was, I want a baby.

(photo credit: Robyn Von Swank)

Jessi Klein is the Emmy and Peabody award-winning head writer and an executive producer of Comedy Central’s critically acclaimed series Inside Amy Schumer. She’s also written for Amazon’s Transparent as well as Saturday Night Live. She has been featured on the popular storytelling series The Moth, and has been a regular panelist on NPR’s Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me! She’s been published in Esquire and Cosmopolitan, and has had her own half-hour Comedy Central stand-up special.

Tags: conceiving naturally, getting pregnancy, having a baby, jessi klein, motherhood, you'll grow out of it