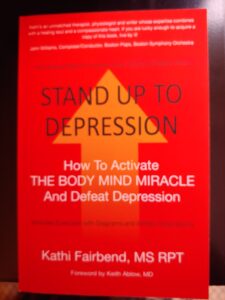

Why Stand Up to Depression by Kathi Fairbend, MS, RPT (Book Excerpt)

In a career spanning decade, I have been astounded to see so many cases of depression intertwined with orthopedic problems, including poor posture. Severe or untreated scoliosis (an “S” type curvature of the spine, from side to side) or kyphosis (an exaggerated forward curvature of the spine) are frequently seen in adolescents and can be the result of untreated osteoporosis in older adults. Both scoliosis and kyphosis, can be discouraging, disfiguring and painful. They can limit a person’s cherished independence. And they can pave the way for depression to take hold.

In a career spanning decade, I have been astounded to see so many cases of depression intertwined with orthopedic problems, including poor posture. Severe or untreated scoliosis (an “S” type curvature of the spine, from side to side) or kyphosis (an exaggerated forward curvature of the spine) are frequently seen in adolescents and can be the result of untreated osteoporosis in older adults. Both scoliosis and kyphosis, can be discouraging, disfiguring and painful. They can limit a person’s cherished independence. And they can pave the way for depression to take hold.

“Sally” had to stop driving at the age of 56 after an auto accident. The collision occurred because her severe scoliosis eventually altered the position of her head, tilting it to one side,

resulting in compromised vision and depth perception. Since she had to give up driving after her accident, which caused some social isolation, Sally suffered a significant depressive episode.

Depression may also be triggered in a child with severe scoliosis who must wear a brace throughout the middle school years. Doctors generally know that untreated scoliosis potentially sets the stage for chronic pain and even damage to internal organs, but fewer focus on the damage to self-esteem that the condition can cause. Back braces themselves can make young people feel damaged and different from their classmates.

Scolions is a far cry from the conditions experienced by Conrad. His depression caused his problems with muscles, joints and posture. In the case of scoliosis in a young person, it is far more likely that the physical problem precedes the emotional fallout. Yet both scenarios can be effectively treated with The Fairbend Method. Why? Because they share a common denominator: Mood affects posture, and posture affects mood.

It’s a complex interplay. Fitness fanatics are another example of a group who can be afflicted by poor posture and, then, by depression. Why? Too often their exercise regimes become unhealthy obsessions that rule their lives. When sidelined by an injury, members of this group—much like a professional skier who is involved in a skiing accident—can descend into major depressive episodes.

Some fitness devotees are prisoners of a vicious cycle. They take up exercise to combat blue or dark moods. When they cycle, lift weights or become marathon runners, endorphins (hormones) in the brain and nervous system are released, reducing their sense of pain. It’s a wonderful, natural way to improve one’s perception of life—until an injury intercedes and makes exercising impossible. Then, the brain ends up starved for those extra endorphins.

When I met “Kara” for the first time she offered her own diagnosis. “I have sciatic nerve problems. My doctor told me I over used my hip muscles and irritated or compressed the nerve. He said it’s called piriformis syndrome. I’ve had it in the past, but now the muscle spasms in my back, buttock area and leg are constant,” she said.

As we talked, I assessed her physical symptoms. She presented with very rounded shoulders. Her head and neck were thrust forward. Kyphosis (the outward curve of the upper back, discussed above) was obvious. Her belly protruded.

Does all this sound familiar? Clearly, this type of posture is not what you might expect of an athlete, but it is common among depressed people.

Depressed mood and low self-esteem may be invisible, but posture is visible and very revealing about mental health.

“I haven’t been able to work out or run for ten days,” Kara said with no small amount of anguish and frustration.

“On a scale of zero to ten, how would you rate your pain?”

“Ten!”

“Okay. Do you remember when the spasms and pain began?” These mishaps can occur even after chores we consider normal or hum-drum.

“Well, I carried two paddle boards up some stairs.”

“From your basement or—?”

“No. We were at the beach.”

“Ah. So, you had to climb those stairs twice and—”

“No,” she scoffed. “I carried them both at the same time. I mean, heck, it was a 75-step climb, after walking in the sand. I didn’t want to do that twice.”

Kara was accustomed to running 30 to 40 miles a week and either biking 20 miles a day or using an elliptical training machine for an hour a day. Her goal was to get in tip-top shape over a 4-month period, so that she could run a marathon to celebrate her 60th birthday. In the previous 6 to 7 months, she had worked with 12 different trainers and performed 8 different fitness routines.

The intensity of Kara’s workout history and mind-set was a red flag. One the toughest aspects of my work is to speak truth to power by explaining to patients with exercise addictions that their excessive exercise is causing them to injure their bodies. They may well have begun as a way to cope with underlying problems of mood.

My first goal was to ease Kara’s painful cycle of muscle spasms so that the tissue could rest and heal. My suggestion to Kara was that she start with a conservative 10-day physical therapy routine. After sharing the details, it was time for me to lower the boom. “Kara,” I told her, “this means you cannot work out or run until you are pain free, and I suggest that you take some anti-inflammatory medications.”

“Uh-uh. No drugs.”

It was her right to decline medications, of course. “Okay, then it’s going to be even more important to ice the area four times daily and rest for up to five hours each day.”

“I can’t do anything?” she asked.

“Sure. You can walk several times a day, outside, for 10 to 15 minutes,” I suggested, hoping this would be enough to appease her zeal for exercise. Then I added three gentle stretches, which she was instructed to do three or four times per day.

“Why the stretches?”

“They’ll help break up the muscle spasms. These are all simple, positive actions that will reduce your pain.”

Withdrawal from any addiction is difficult. Kara’s dependency on physical exertion was as strong as any I’d seen. She teared up, but said she would go forward with the plan.

Days later, on a follow-up visit, Kara was accompanied by “Vince,” her husband. She rated her pain at 7, a significant drop since her first visit, but Vince had other things on his mind.

“I have connections in the medical community,” Vince said. “I can get any surgeon you think is suitable.” This was not a direction I was ready to recommend, but he persisted. “Kara feels like her life has ended. She wants us to sell the house and move into a condo. I’m not ready for that. We’re not ready. We’ve got to do something.”

The need to act in a time of crisis is understandable. Yet if the affliction— depression—remains invisible, the action taken may miss the mark.

Kathi Fairbend MS RPT, author, physical therapy and ergonomic consultant, is a graduate of Boston University (M.S.) and Tufts University (B.S.). Kathi’s practice includes patient care, teaching and ergonomic consultation, with individuals and corporate clients throughout the country. For 11 years Kathi has been the ergonomic consultant for the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University.

Kathi Fairbend MS RPT, author, physical therapy and ergonomic consultant, is a graduate of Boston University (M.S.) and Tufts University (B.S.). Kathi’s practice includes patient care, teaching and ergonomic consultation, with individuals and corporate clients throughout the country. For 11 years Kathi has been the ergonomic consultant for the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University.

Kathi taught at Northeastern University’s, Bouve School of Health Sciences, Boston University and Simmons College, and was advisor for the entrepreneurial program at Babson College. She is a Life Member of the American Physical Therapy Association and the first American physical therapist to present pre and post-operative treatment for total hip patients at the Association’s National Conference. The Fairbend Method, described in STAND UP TO DEPRESSION, to achieve sound posture, which affects mood, can have immediate and positive results.

Tags: depression, kathi fairbend, mom self care, raising a child with depression, scoliosis, stand up to depression, the fairbend method