Guest Blog Post: BEYOND THE TIGER MOM: East-West Parenting for the Global Age by Maya Thiagarajan (Book Excerpt)

LEAVING THE GARDEN OF EDEN: Metaphors for childhood

LEAVING THE GARDEN OF EDEN: Metaphors for childhood

Childhood is often romanticized in Western literature. It is a time of unlimited freedom and beauty; a utopian, Edenic paradise. Much like Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, children play happily in the garden of childhood, blissfully unaware of all the problems and evils that lurk in the adult world. Barefoot and splashing through puddles, children live in the moment and experience the world entirely

through their senses. With ice cream smeared all over their faces and chocolate stains on their shirts, they are unconcerned about how they look or behave. In their innocence and joy, they assume that they are beautiful and lovable. As they look into our eyes for protection and assurance, they assume, too, that all adults are good people who will care for them and not hurt them.

Unfortunately, like Adam and Eve, all children will at some point eat of the forbidden fruit, gain knowledge of the adult world, and then be forced to leave their blissful paradise. As children grow up, they will inevitably encounter rejection and failure, hurt and betrayal. They will gain knowledge of troubling concepts like poverty, injustice, discrimination, and cruelty. As they experience the full range of adult emotions and experiences—love, sex, jealousy, rage, regret, hurt, betrayal, empathy, compassion, loss, grief—they will gain knowledge of good and evil, and they will, slowly but surely, be forced out of their magical garden, never to return to it again.

In Asia, too, childhood has historically been idealized and romanticized. The Confucian image of childhood as a time of purity is captured in the saying, “Children are like white paper.” Across Asia, proverbs celebrate the beauty and divinity of childhood: “There is no treasure that surpasses a child,” and “Until seven, children are with the gods.”

In Indian mythology, childhood and its beauty are often embodied in stories about the deity Krishna as a child. He would steal butter, play naughty pranks on the milkmaids, and constantly get himself into trouble. Yet, no one could be angry with him—partly because he was divine and partly because he was, after all, a child. Children were seen as the embodiment of innocence and joy; one was expected to laugh and smile at a child’s mischief.

A particularly poetic metaphor in Eastern stories is that of a parent rowing her child across a river or helping him cross the bridge from childhood to adulthood. The river is dark and dangerous, and the parent must accompany the child on this difficult journey from innocence to experience, from immaturity to maturity. If he were to cross the river alone, he would feel sad, lonely, and scared, so it is essential that the parent experience the journey with him. In that sense, many traditional Eastern metaphors for childhood center on protection: the parent must protect the child and accompany him on the journey through childhood and into adulthood.

More contemporary metaphors for childhood, not just in Asia but in big global cities around the world, seem to lack such pathos and poetry. They focus on training grounds, boot camps, battlefields, and stock markets. Children become little soldiers, wielding their laptops, pens, and backpacks, as they march to and from school and tutoring sessions, following instructions and firing out answers to test questions. Twenty-first-century life seems like a battleground to us parents: harsh, hostile, competitive and cruel. We need to train and equip our little soldiers so that they can work for a big multinational company in the future. The rhetoric in education, in both East and West, has become so corporatized that people think nothing of articles that use “What Google Needs” or “Employees of the Future” as a basis for dictating what should be taught in schools. In fact, it is big corporations, particularly technological ones, that now drive curricula and education policy.

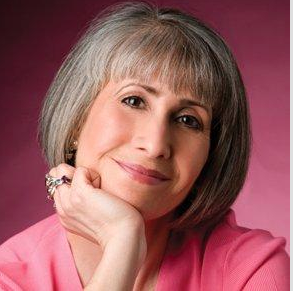

A global citizen, Maya Thiagarajan has lived and worked in India, Singapore, and the US. She earned a BA in English from Middlebury College and a Masters in Education Policy from Harvard University.

A global citizen, Maya Thiagarajan has lived and worked in India, Singapore, and the US. She earned a BA in English from Middlebury College and a Masters in Education Policy from Harvard University.

Maya began her teaching career with Teach For America, where she taught at a public school in Baltimore City. She went on to teach high school English at some of America’s most prestigious independent schools. After a decade teaching in the US, Maya moved to Singapore and taught at The United World College of South East Asia.

Struck by the different approaches to education and parenting she encountered, Maya began to interview Chinese and Indian parents in Singapore. Using her experiences as well as the stories of other parents, she wrote Beyond the Tiger Mom: East-West Parenting for the Global Age, where she looks at Western and Asian approaches to parenting and education.

Maya also conducts workshops for parents and teachers on education related topics.