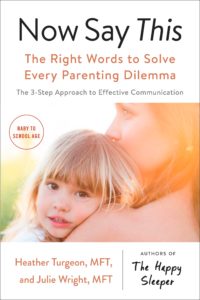

Now Say This by Heather Turgeon, MFT, and Julie Wright, MFT (Book Excerpt)

Health and Development

Health and Development

The research on how screens relate to health and development is complex. We can’t lump all screens together (watching a movie is different from building a world in an interactive game, which is different from blasting zombies with a console). What kids are watching, for how long, at what age, and in what context all matter.

We do have some information to help us make good choices, though. For example, we know that baby brains are programmed to learn from experimenting with the physical world. Infants learn physics from simple activities like rolling a ball and banging spoons; numbers and math concepts by putting blocks into a container or building a tower; and language from adults making eye contact, gesturing, and interacting as they talk. It’s not just babies; little kids learn from the physical world too, and from having unstructured playtime in which they can create imaginary worlds, develop relationships, make plans, and follow through on ideas. Screen time is not necessarily bad, but for little kids, most other activities (even rolling around in the grass or snow) are better. The question of whether babies and little kids can learn from media and screens continues to be researched—it’s likely that they can learn from quality educational media, especially when adults watch and interact along with them.

In our experience, though, most parents don’t use screens this way. They (understandably) turn on a screen while they take a break to do house chores, eat quickly, or take a shower. In that case, the latest recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics are to avoid the use of screen media, other than video chatting, for children younger than eighteen months; and for toddlers between eighteen and twenty-four months to choose high-quality programming and apps, and to interact with the child when using them. Between ages two and five years, the recommendation is to limit screen time to one hour per day, of high-quality programming.

Increased screen time is associated with higher body mass index and obesity rates. Again, it’s hard to tease out which comes first, screens or sedentary tendencies. Screen time can also lead to mindless eating out of habit and consumption of higher-calorie snacks (which many of us adults can empathize with!).

Primed for Meltdowns

Many of the video games on the market today are masterpieces of entertainment. They’re immersive, they’re exciting, they feel as though they should never end. When kids play, the world falls away and their minds are swept up. The nervous system goes on high alert—a dragon, a ninja, the next level, a pile of gold! Neurochemicals like dopamine are released, leading to a feel-good state and a desire to keep going. Many games even encourage frequent checking in and use so as not to miss out on extra points or benefits that arise randomly.

When it’s over, other activities can seem less interesting and enjoyable. Stress hormones that raged during the epic dragon battle still course through the body. Sometimes video games can leave kids feeling mentally depleted and emotionally dysregulated. This can appear as a child being withdrawn, bored, or tantrum-prone. Parents tell us that their otherwise rational child is practically unrecognizable when it comes to screens. Other parents report what looks like a cycle of behavior problems and screen use: Kids who have trouble sitting still and regulating emotions are sometimes given screens to distract, soothe, and calm them down. In turn, when the screens go off, the problem has compounded.

This may sound like we’re saying video games are bad, but the issue isn’t one-dimensional. For example, research also shows that action video games can improve certain aspects of attention and multitasking ability. Precisely those powers that make video games so powerful can also be used for good. Video games are being developed to improve certain brain functions, and elevate learning. There are many companies developing games that are constructive and teach skills. Not surprisingly, research shows that most parents of older children agree that technology positively supports their kids with schoolwork and education, that technology helps them learn new skills and prepares them for future jobs.

So media and screens are powerful and multidimensional. It helps to be aware of how they affect your child’s emotions and behaviors; to choose family practices that take good care of eating and sleep; and to protect time for unstructured play in the real world. Again, our focus in this chapter is to move beyond deeming screens as good or bad, and to help you think about their role in your family and their effect on your particular child. After you make decisions about family rules and habits around screens, we’ll help you navigate common stuck moments and conversations about their use.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Heather Turgeon, MFT is a psychotherapist who specializes in sleep and parenting. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times and The Washington Post, among others. She lives in Los Angeles with her husband and two kids. She and Julie frequently speak at parenting centers and schools, and offer sleep consultations and individual therapy.

Julie Wright, MFT is the creator of the Wright Mommy and Me, one of Los Angeles’ best known mommy and me programs. She has specialized training and experience in the 0-3 years, interning at Cedars Sinai Early Childhood Center and LA Child Guidance Clinic. She divides her time between Los Angeles and New York City and has a son in college.

Now Say This: The Right Words to Solve Every Parenting Dilemma,copyright 2018, is published by TarcherPress, a division of Penguin Random House, Inc.