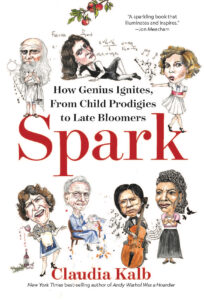

Spark: How Genius Ignites, from Child Prodigies to Late Bloomers by Claudia Kalb (Book Excerpt)

The enigmatic circumstances of our lives—where we’re born, when we’re born, to whom we’re born—are defined by some measure of luck. Parents, teachers, and mentors play a pivotal role and come in myriad forms. Sara Blakely turns to a motivational speaker to help guide and buoy her. Roosevelt, orphaned at the age of nine, found comfort and counsel in an educator who nurtured her self-reliance and confidence. Gates’ parents supported him even when he decided to leave Harvard in his junior year to start Microsoft. “I knew it was safe to try new things,” he tells me, “because they were there for me.”

The enigmatic circumstances of our lives—where we’re born, when we’re born, to whom we’re born—are defined by some measure of luck. Parents, teachers, and mentors play a pivotal role and come in myriad forms. Sara Blakely turns to a motivational speaker to help guide and buoy her. Roosevelt, orphaned at the age of nine, found comfort and counsel in an educator who nurtured her self-reliance and confidence. Gates’ parents supported him even when he decided to leave Harvard in his junior year to start Microsoft. “I knew it was safe to try new things,” he tells me, “because they were there for me.”

Timing and serendipity are often keys to success. Child discovered French cooking because her husband got a diplomatic job that landed them in Paris. Grandma Moses’ unlikely success as an octogenarian folk artist depended on a collector happening upon her paintings at a drugstore in Hoosick Falls, New York. Shirley Temple’s career as a child star coincided with America’s desire for an antidote to the Great Depression. Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin might never have happened if he hadn’t left his lab dishes out on his worktable during a summer vacation.

In my research, I discovered numerous fallacies about how creative triumph comes to be. The notion of lone genius mythologizes the journey to achievement and has been replaced with an understanding that collaboration, in one form or another, is vital to the pursuit of new ideas. Newton’s revelations did not emerge solely from the depths of his own knowledge; he built on the foresight of scientists who came before him, including Copernicus, Galileo, and Descartes. Gates created Microsoft with Paul Allen and started his philanthropic foundation with his wife, Melinda. Angelou had an editor in Robert Loomis, who prodded her to write her first book and then encouraged and supported her through dozens more over their four-decade partnership. When he retired in 2011, she remarked, “I can’t imagine trusting a manuscript in the hands of anyone else.” Ma dedicates much of his musical performance to collaborations with other musicians; his 2020 album, Not Our First Goat Rodeo, unites him and his cello with instrumentalists who play fiddle, banjo, mandolin, guitar, and bass. They learn from one another.

There are misperceptions, too, about how talent plays out. The prodigies in these pages all exhibited an adeptness nurtured by parents, but they were also gripped by a fascination for their craft and worked hard to improve. Picasso never stopped experimenting, painting at all hours of the night. Ma was born to musical parents who recognized his ability, but he still had to sit at the cello and practice; his joy of playing kept him going. Temple had an endearing brightness and appeal that captivated her audience, but she knew what was required to excel. “The rules were simple,” she later wrote. “Hang on, keep tap shoes at the ready, and don’t spill milk in the car.”

Life trajectories do not follow a standard pattern. Most child prodigies do not grow up to be geniuses, no matter how flawlessly they master a skill; often, their solitary focus on a subject leaves them detached from peers and unable to navigate stresses as they age. Still, some prodigies do excel later in life, sometimes by choosing entirely new professions. After Shirley Temple retired from acting in early adulthood, she got married, raised three children, and kicked off a diplomatic career at the age of 41 that lasted more than two decades— the case of a prodigy and midlifer all in one.

Many readers will be pleased to discover that, yes, there is still time. The middle decades of life, long reputed to be the crisis years, may serve as a reawakening—a period when inadequacy and self-doubt dissipate and confidence and happiness surge. For the midlifers in these pages, the accumulation of decades brought courage and wisdom. Julia Child capitalized on her middle-agedness to entice her fans. Alexander Fleming’s years of scientific know-how prepared him to recognize the significance of his findings. “The 50s,” Maya Angelou told Oprah Winfrey, “are everything you’ve been meaning to be.”

For those who despair about aging and fear an inevitable slow- down, consider the experiences of Roosevelt, Roget, and Moses. The first lady spearheaded the passage of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights at the age of 64. Roget, trained as a doctor, launched his second career writing and revising his thesaurus in his 70s. Moses spent most of her early life working on a farm and raising children; she turned to painting as a grandmother seeking a sense of purpose. “I have been painting a long time,” she told the New York Times in 1945, the year she turned 85. “I better try something else. Perhaps I shall start building houses.”

In the years to come, we may well learn more about our life trajectories from a biological viewpoint. Neuroscientists are looking for clues into how the “aha moment” transpires at the cortical level and how traits like resilience surface. Investigations into how the brain ages are revealing evidence that our neurons are far more proliferative than previously thought, allowing for more learning and growth at later stages in life. These studies cannot change what gives us joy or who we want to be. But they may provide intriguing insights into what we are capable of doing.

My hope is that these profiles will not only illuminate the many junctures at which discovery can happen, but will also inspire those who are still searching for fulfillment. Some lives are linear while others zigzag; some embrace a childhood love, while others find fulfillment in retirement. Every figure in these pages proves to be wholly human, filled with his or her share of missed opportunities, defeats, insecurities, and bouts of unhappiness.

One thing we can learn from these individuals is that the traits we most admire in others do not always come easily and we may need to be intentional about choosing them for ourselves. To this end, Blakely tells me she sets out to be courageous. Ma and Angelou, who called herself “a contrived optimist,” make a determined point of being positive. “I have to really work very hard to find that flare of a kitchen match in a hurricane and claim it, shelter it, praise it,” Angelou once said. Genius need not be vaulted onto a pedestal.

Excerpted from Spark: How Genius Ignites, from Child Prodigies to Late Bloomers, by Claudia Kalb. Copyright © 2021 by National Geographic Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpted from Spark: How Genius Ignites, from Child Prodigies to Late Bloomers, by Claudia Kalb. Copyright © 2021 by National Geographic Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Claudia Kalb is an independent journalist and author of the New York Times bestseller Andy Warhol was a Hoarder: Inside the Lives of History’s Great Personalities (National Geographic Books, 2016). Her new book, Spark, builds on a series of cover stories she wrote for National Geographic about the origins of genius. Spark explores moments of discovery in the lives of 13 great achievers, from Pablo Picasso and Yo-Yo Ma to Maya Angelou, Julia Child and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Tags: andy warhol, career pivot, child prodigy, claudia Kalb, eleanor roosevelt, genius, julia child, late bloomer, maya angelou, midlife, midlife succcess, new york times, pablo picasso, reinvention, sara blakely, Spark