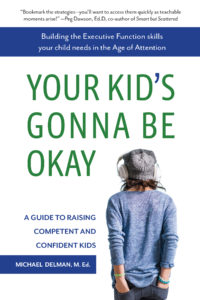

Your Kid’s Gonna Be Okay: Building the Executive Function Skills Your Child Needs in the Age of Attention by Michael Delman (Book Excerpt)

Clueless: How to Upset the Teacher Without Really Trying

Clueless: How to Upset the Teacher Without Really Trying

So this obnoxious teenager walks into the classroom. And he’s sitting there whispering to his friend as the teacher tries to lead the class in what anyone would agree is a very good lesson being taught by a true pro. And the teacher is trying to hint ever-so-nicely to the student, with various looks, and gestures, and the clearing of his throat, and so on, that this student, who seems to think that his conversation is more important than anything the teacher is offering, needs to make better choices and focus on the issue at hand. But the kid goes on until finally there is no choice, really, but to say something directly to the student, even though it will interrupt the flow of the excellent lesson.

So the teacher looks at the student and says, “Mr. Delman, am I interrupting your conversation with your friend?”

And I look up at the teacher and say, “Yeah, but I’m gonna let it go this time.”

And then the teacher, who is known for having an amazing sense of humor, does not give me a high five for cleverness or even laugh. He does not move on. He looks surprised and maybe hurt, as if I have betrayed him, and he sends me to the principal’s office, a place I have been before but not since middle school. Question: what went wrong?

Well, some of my wise-guy response was simply me trying to show off for a laugh, but my rude behavior also had to do with my attention difficulties. Initially, I was distracted by the opportunity to talk to a friend. Then, I ignored the various cues to get back on track; I observed them, but I didn’t feel the sense of urgency needed to tune into the teacher. It wasn’t just that I chose to ignore him. It was that my friend whispering to me seemed louder than the teacher speaking at full volume to the class. The teacher was talking generally; my friend was whispering specifically to me. That made a difference in what got my attention. When the teacher did address me directly, he definitely got my attention, but I wasn’t thinking about the appropriate context. I replied impulsively with the first idea that popped into my head.

As understanding as I am of kids who cross the line as I did that day, I am well aware of the fact that the detention I received was a fair response. What was helpful was this teacher meeting with me to ask what I thought would be a good solution. I decided not to sit near my friend anymore, something I have a feeling would have been the result even if I hadn’t come to that conclusion on my own. This teacher was masterful and allowed me to grow from the experience instead of relying only on his power to punish me. I’m sure he is one of the reasons why I went on to become an educator.

Kids with impulse control and attention challenges, some of the most fundamental of Executive Function skills, will need to develop tricks, tools, strategies, and discipline. Even those who take medication still need the skills just as those who wear glasses still need to learn how to read. Some of those skills, such as the pants technique in the next section, and specific note-taking strategies, such as those covered later in this chapter (see “Pushing Boundaries: How to Focus through Challenge”), are preventative. Doing them removes temptations so that our children can focus. Others, such as learning to apologize and to reflect on and change what is not working (see chapter 6), are used after a problem has occurred as a learning experience.

It is worth bearing in mind the upsides to having challenges with impulsivity and/or attention if your child learns to master them. In education and in science, in business and in politics, there is a growing interest in neurodiversity, an approach to our brain differences that finds the pros and cons of various learning profiles so that we can all capitalize on our strengths and manage our weaknesses. People with adhd, or who have a profile like someone with adhd, often have great creativity and make novel connections. Many possess a certain charisma that can allow them to motivate others. They can have energy to persist on hard work that can astonish others . . . as long as they’re not bored. For myself, diagnosis or not, the challenges and benefits of this sort of fidgety energy have led me to want to help kids do better, something I certainly did not imagine doing when I was a little  whippersnapper mouthing off to teachers I adored. Maybe it’s karma.

whippersnapper mouthing off to teachers I adored. Maybe it’s karma.

Massachusetts Distinguished Educator Michael Delman is founder and CEO of Beyond BookSmart, LLC, the first organization to apply Dr. James Prochaska’s Transtheoretical Model of Change to help students improve academic performance.

One Response to “Your Kid’s Gonna Be Okay: Building the Executive Function Skills Your Child Needs in the Age of Attention by Michael Delman (Book Excerpt)”

As a former teacher, I think the student’s response was funny albeit not on target. I would not have sent him to the principal, I would have nabbed him after class and asked him to see me that afternoon.

There is no need to escalate the situation by bringing in the big guns.

By ADB on Jul 12, 2018