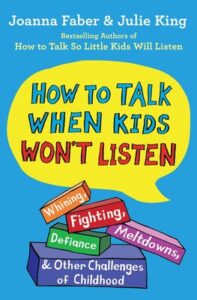

HOW TO TALK WHEN KIDS WON’T LISTEN By Joanna Faber and Julie King: Interview with the Authors by Melissa Couch Salim

This is such a great book. I love the sample conversation that shows the dos and the don’ts. You start by talking about feelings, which is a BIG topic, especially with toddlers and teens. What are a few top basics that we might remember and practice? It’s stressful when our kids express negative feelings to us. We don’t want our kids to feel angry… disappointed… frustrated! Our tendency is to explain to our kids why they shouldn’t feel that way, it’s not that bad, you’re overreacting. The counterintuitive truth is that it actually makes kids (and, in fact, people!) feel better when someone acknowledges their negative feelings.

This is such a great book. I love the sample conversation that shows the dos and the don’ts. You start by talking about feelings, which is a BIG topic, especially with toddlers and teens. What are a few top basics that we might remember and practice? It’s stressful when our kids express negative feelings to us. We don’t want our kids to feel angry… disappointed… frustrated! Our tendency is to explain to our kids why they shouldn’t feel that way, it’s not that bad, you’re overreacting. The counterintuitive truth is that it actually makes kids (and, in fact, people!) feel better when someone acknowledges their negative feelings.

It might be helpful to try this approach out on yourself, before trying it on your kids. Imagine that you come home from work and say to your spouse: My boss is such a jerk. (And maybe you use a stronger word than “jerk”) He screamed at me in front of all my coworkers for not finishing a report that he gave me to do at the last minute, with no time to complete it.”

How would you feel if your spouse replied, “Hey, calm down. You’re overreacting. I’m sure it’s not that bad. Your boss was probably just under a lot of stress. You’re going to have to get over it. You know you need this job. And by the way, we don’t use the word “jerk” in this family. It’s disrespectful.”

Did you find your anger at your boss morphing into hostility for your partner?

Now imagine that your partner responds in a different way.

“That sounds really stressful and frustrating! To be reprimanded in public for something that isn’t even your fault is so unfair.”

Did you feel a little better? You may have a “jerky” boss, but at least you have an understanding partner who is on your side. Maybe after a little more venting you will even feel calm enough to think about a strategy for handling a situation like that in the future.

What would this sound like when talking to a child?

When your toddler gets terrified during a thunderstorm, instead of saying: “Hey, come on. Be brave. Thunder can’t hurt you!”

Try: “Thunder can be scary. It’s so loud! You’ll be glad when it’s over.”

That second response will be much more comforting and will actually help a child handle her fear.

When your child says: “No fair, Sissy ate the last peanut butter granola bar and those are my favorites!”

Instead of replying: “Well, guess what? Life is unfair. No use whining about it. Have one of the blueberry bars.”

Try: “Oh that’s disappointing! You were really looking forward to eating one! I’m going to write it down on our shopping list so we don’t forget to buy more.”

The second response is much more likely to help your child move on from disappointment.

When your middle-schooler frets: “I’m never going to finish this paper on time. It’s too much!”

Instead of: “Well I told you to start earlier. You just didn’t listen!”

Try: “It’s a big project. There are so many parts to it, it can be hard to get started.”

That second response is more likely to give your child the courage to face an overwhelming task. The first response is likely to demoralize him even further.

When your teen says: “I don’t care if I fail algebra. It’s totally irrelevant to my life.”

Instead of: “You’re too ignorant to know what’s relevant and what isn’t relevant to your life. I’ll tell you one thing, it’s going to be extremely relevant when you go and apply for a job and you don’t even have a high school diploma because you didn’t do your algebra homework.”

Try: “If it were up to you algebra would NOT be required. It would be nice to be able to choose what you study.”

Getting kids to cooperate on our time often seems an impossible feat. You write about making it fun and providing choice. Can you elaborate? Kids don’t like to be ordered around. (In fact, the same could be said of people in general.) And yet we need kids to do so many things — put your shoes on, pick up your toys, get in the car, … the list goes on and on. Instead of issuing commands, it can help to be playful. Make those shoes talk (“I feel so empty. I need a foot in me”), turn the drudgery of clean-up into a game (“Let’s see if you can get all the Lego in the bin before I finish chopping these carrots. Ready, set,… go! … How did you beat me again?”) If you don’t have the energy to be playful, try offering a choice: ” Do you want to hop to the car…. Or skip? Do you want to walk to the car the regular way….. or backwards?

You dedicate a chapter to the topic of punishment. It’s been such a controversial subject for as long as I can remember. So, your belief is that punishment can make matters worse? The short answer is that there are a lot of downsides to punishment, and there are better alternatives for handling conflict. We think we need to punish kids so they’ll “learn their lesson,” but more often punishment encourages children to think selfishly. Instead of focusing on fixing the problem or making amends, punishment causes them to focus on their own resentment. How much time will they be grounded? How much TV will they miss? How can they avoid getting caught in the future? Punishment can actually be a distraction from the lesson we want them to learn.

Adults today were most likely punished. What residual effect does it leave for those who were punished and even spanked and whipped? According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, based on their review of decades of studies, there is overwhelming evidence against the use of physical punishment, including spanking with an open hand. These studies found that physical punishment was associated with higher levels of aggression against parents, siblings, peers and spouses, in addition to increased incidence of depression and anxiety, disruptions in parent-child attachment, increased use of drugs and alcohol, slower cognitive development, lower academic achievement, and higher levels of antisocial behavior. And these effects are not just seen right after the punishment occurs. They last into the teen years and even adulthood.

What is the biggest challenge for parents today? Parents are trying to do it all — working and taking care of kids, often without the support of nearby family or community. And now with the pandemic, they are often doing those two things simultaneously, which is even more challenging, and sometimes borders on the impossible.

What inspired the book? After we wrote How To Talk SO LITTLE Kids Will Listen, we started to receive emails from all over the U.S. and the world — parents in Russia, Slovenia, Singapore, India, England, South Africa — telling us that they read our book and sharing stories of how they used the communication tools with their kids. They also asked questions that hadn’t been directly addressed in our book — about how to handle conflicts over screen time, or pets, or name calling, or divorce. At one point we had so much material we decided to put it into another book. How To Talk When Kids Won’t Listen is a combination of stories from real parents around the world and a sort-of advice column where we publish the actual letters and our answers. A lot of parents told us that they wanted a way to practice this How To Talk approach, so we added interactive material — exercises and quizzes for those who are in the mood to put pencil to paper.

What it boils down to is, it’s one thing to know the theory. It’s another thing to put that theory into practice, in the moment, under stress. Especially if these aren’t the words that come instantly to mind. It’s enormously helpful for parents to hear how other people have used these strategies in a variety of situations.

Do you offer parents one-on-one training? Yes, we offer one-on-one (or two-on-one for couples) phone and video support. We also offer online workshops, which provide participants with the opportunity to practice and ask questions in interactive sessions, and we hope to be able to offer in-person workshops again in the post-pandemic future. You can get more information at how-to-talk.com.

You can also go to the website to get an additional free chapter of the book that walks parents through how to talk when your parenting partner will not listen.

About the Authors

Joanna Faber and Julie King are the authors of the new book, How To Talk When Kids Won’t Listen: Whining, Fighting, Meltdowns, Defiance, & Other Challenges of Childhood, as well as the best-selling book, How To Talk So Little Kids Will Listen: A Survival Guide to Life with Children Ages 2-7, which has been translated into 22 languages world-wide. They created the app HOW TO TALK: Parenting Tips in Your Pocket, a companion to their book, as well as the app Parenting Hero. Together they speak to schools, businesses and parent groups nationally and internationally, they lead “How To Talk” workshops and support groups online and in person, and provide private consultations. Visit them at How-To-Talk.com, on Facebook @faberandking or on Instagram @howtotalk.forparents.

Tags: fatherhood, having family, how to talk when kids won't listen, later motherhood, parenting, raising children, teens, Tweens