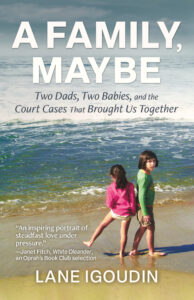

Pathways to Parenthood (Excerpt from A Family, Maybe: Two Dads, Two Babies, and the Court Cases That Brought Us Together) by Lane Igoudin

My earliest knowledge about gay parenting comes from, of all places, Newsweek. Back in 1996, working a student job at Stanford News Service, I picked up a glossy issue from a stack of magazines that came in, intrigued by the cover blurb, “Gay Families Come Out.”

My earliest knowledge about gay parenting comes from, of all places, Newsweek. Back in 1996, working a student job at Stanford News Service, I picked up a glossy issue from a stack of magazines that came in, intrigued by the cover blurb, “Gay Families Come Out.”

Those were different times for gay people in America. While the decades of criminal persecution had largely ended, full equality was still years away. Just two months before the article’s publication, President Clinton signed into law the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), prohibiting federal recognition of same-sex unions. The Newsweek’s five-page feature, complete with a star interview (Melissa Etheridge and her partner), and a normalizing, the-kids-are-alright narrative of a daughter of a gay mom, gave the readers the true lay of the land.

In 1996, only 13 states allowed lesbian women and gay men to adopt. California, my home state, along with Ohio and some New England states, was colored the “highly tolerant” green on the map accompanying the article. “Even then,” the writers noted, “usually only one partner is the parent of record—leaving the other in legal limbo. Courts allowed adoptions by a second parent in some of those states, although the law is still in flux.”

“Flux” characterized the state of being a gay parent. In some states, one could still lose a child, even one’s own biological child, because of being a homosexual. To protect their children and families, many gay parents had to stay in the closet. But some began to confront their kids’ schools and other public institutions to demand acceptance.

The Newsweek article sparked hope in me; there was a way for a gay man to have children, and luckily, I was living in a green state.

I saved the clipping and started a file, but I wasn’t ready. As a single gradstudent living in San Francisco, I never saw myself as anyone’s husband. Relationships would come and go without affecting me deeply, but what I saw, like a prophecy within, was an image of a single father with two kids. Entering the adoption process years later was simply following my inner path. I knew I would never be fulfilled if I didn’t have kids.

Gay men with children were still rare—a novelty, fitting poorly into the sexual politics of the time, when refusal to procreate remained a pillar of homosexual identity, an unambiguous divider between the oppressor and the oppressed. “Be gay. Don’t breed,” read a fridge magnet sold in the city’s gay neighborhoods. Parenting wasn’t for us. Persecuted, marginalized, disempowered, and discriminated, we were at least freed from the toils of raising children. Would gay parenting be the ultimate betrayal of our special destiny, or the ultimate proof of our emancipation? The community’s attitude was ambivalent.

One year later in 1997, Jonathan and I met in San Francisco and fell in love. Our dating was breathtakingly romantic, and our relationship grew ever more passionate with every week and month. But from the very start, Jon made it clear that becoming a dad wasn’t on his agenda. “With nine siblings and 25 nieces and nephews,” he told me, “I don’t particularly feel like I need to have my own children.”

His lack of interest in parenthood couldn’t dampen my curiosity. Two years passed, and in the midst of Jon’s transferring within his insurance firm to Southern California to live with me, I dropped by a Maybe Baby meeting in West Hollywood for prospective LGBT parents. Adoption options, support groups, helpful attorneys—in Los Angeles, the process seemed less politicized, more manageable. I scribbled down as much information as I could, along with the phone number of a representative from the PopLuck Club, LA’s gay dad organization.

The following month, Jon moved down the coast. After two years of weekend commutes, we were finally living together and in true bliss. Outside our spacious apartment, the city lights never dimmed, nor did the palm trees ever stop swaying gently by the sandy beach across the street. Neither of us had ever lived with a partner, so it was time to really get to know each other, to scale down personal demands, to divide the household minutiae, to interweave our cultures—my borscht and his upside-down pineapple cake, my Shabbat dinners and his Christmas tree.

Soon we bought our first home: a Mission Craftsman bungalow, a short walk from the beach. We fit perfectly with the neighborhood: a preppy gay couple, nights out at art openings, shows, clubs, globe-trotting from Prague to Venice to Machu Picchu. We were fortunate; life was busy, but not hard. During the day, I was managing communications at a private hospital, and in the evening, in our bougainvillea-covered bungalow, I would escape into writing the novels that I would try, disastrously, to get published. Meanwhile, my by-line started to pop up in local magazines under a stream of music and theater reviews around Los Angeles and out of town.

Good times didn’t dim my vision of becoming a father. I joined an online gay adoption listserv, entering a pipeline of stories, questions, and tips. California was still a “highly tolerant” state compared to those places where people like me had to hide their partners during home study inspections.

A gay dad got profiled in a local magazine. I highlighted his story throughout: his step-by-step foster-to-adopt path, his desire to have a set of siblings so that the kids would always have a blood relative no matter what happened. The resource list accompanying the article included the foster parent recruitment office of the Los Angeles County.

Now, in my early thirties, armed with information, I felt ready to pursue parenthood. But “I” wouldn’t be enough, it had to be “we.”

Lane Igoudin, Ph.D., is the author of A Family, Maybe, a journey through foster adoptions to fatherhood (Ooligan Press, 2024). He has written extensively on foster adoption, parenting, and LGBTQ issues for Adoption.com, FamilyEquality.org, Forward, Lambda Literary Review, and LGBTQ Nation, and spoken about his book on NBC’s “Daytime” show as well as a variety of syndicated radio shows and podcasts. Lane is professor of English and linguistics at Los Angeles City College and recently served as an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow with the Humanities Division of UCLA. Visit www.LaneIgoudin.com

Lane Igoudin, Ph.D., is the author of A Family, Maybe, a journey through foster adoptions to fatherhood (Ooligan Press, 2024). He has written extensively on foster adoption, parenting, and LGBTQ issues for Adoption.com, FamilyEquality.org, Forward, Lambda Literary Review, and LGBTQ Nation, and spoken about his book on NBC’s “Daytime” show as well as a variety of syndicated radio shows and podcasts. Lane is professor of English and linguistics at Los Angeles City College and recently served as an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow with the Humanities Division of UCLA. Visit www.LaneIgoudin.com

Tags: adoption, family, foster adoption, gay couple, later fatherhood, parenting